By Ed Feld, senior editor, Siddur Lev Shalem for Shabbat & Festivals

Translating can be a dangerous business. The great English translator of the Bible, William Tyndale, whose work formed the basis for the King James Version, was martyred in 1534 during the reign of King Henry VIII. Tyndale was responsible for some lovely innovations in language such as ‘lovingkindness’ for the Hebrew hesed -- a trait clearly not exercised by his detractors. Today’s critics of translation may be less violent but no less passionate about what they consider right or wrong about translations.

Translating can be a dangerous business. The great English translator of the Bible, William Tyndale, whose work formed the basis for the King James Version, was martyred in 1534 during the reign of King Henry VIII. Tyndale was responsible for some lovely innovations in language such as ‘lovingkindness’ for the Hebrew hesed -- a trait clearly not exercised by his detractors. Today’s critics of translation may be less violent but no less passionate about what they consider right or wrong about translations.

In translating the new Siddur Lev Shalem I’ve been guided by certain principles prefigured by the translations in the new mahzor and seconded by the current siddur committee. I’ve tried to find an English language register which conveys the simple and direct quality of the Hebrew. The committee was clear that we were not to hide passages which might be problematic, covering them over with vague formulas – m’hayeih ha-meitim is translated as “giving life to the dead,” not “master of life and death.” Most of all, I’ve tried to avoid “prayerbook English” – words that one meets only in the prayerbook but which have no correlation with daily language. Tyndale’s felicitous “lovingkindness” had to go (as I type this, my spellchecker tells me that it is not a correct English word!) because it no longer conveys meaning – people read it and their eyes glaze over, it is a word which no longer describes a behavior they can correlate.

Sometimes though, literal doesn’t work. I’m currently working on the translation of Hallel and struggled with the opening verse of psalm 11 -- B’tzeit yisrael mi-mitzrayim, usually translated as ‘when Israel went out of Egypt.’ While it is true that this is a word for word translation, it in no way captures the nuance of the Hebrew. Yitziyat Mitzrayim in the Jewish imagination never meant simply “leaving”, as if we had visited Egypt and now were journeying to other sites in the Middle East. Robert Alter does a bit better with “When Israel came out of Egypt” --one comes out of a difficulty -- nevertheless, I thought the phrase was a bit clumsy and did not scan well. “When Israel escaped from Egypt” was a possibility, but this seemed like it was saying too much. Finally, talking it through with our committee, we settled on “When Israel was liberated from Egypt,” that conveyed all of the overtones of meaning associated with this phrase in the course of Jewish history. We’re translating a prayerbook, not the Bible, and the meanings of phrases built up over time are as important to us as the original definition.

Preserving a poetic sensibility is an equal consideration. Building on what some translators have done, I’ve offered at the end of that psalm, “turning palisades to pools, flint to fountains,” the alliteration standing in for the rhythmic quality of the Hebrew lines.

And, oh yes, since I couldn’t use Tyndale’s “lovingkindness,” I’ve had to make do with substitutes -- sometimes I translate it as “kindly love” sometimes as “kindness and love,” sometimes simply as “love.” I’ve certainly not done better than Tyndale but hopefully these words will speak to a modern reader in a way that his remarkable inventiveness no longer can.

Translating is an art, not a science, and art evokes passionate responses. I’d love people to feel passionate about a siddur hopefully with emotions expressing love and kindness, not anger. I’m not courting martyrdom after all.

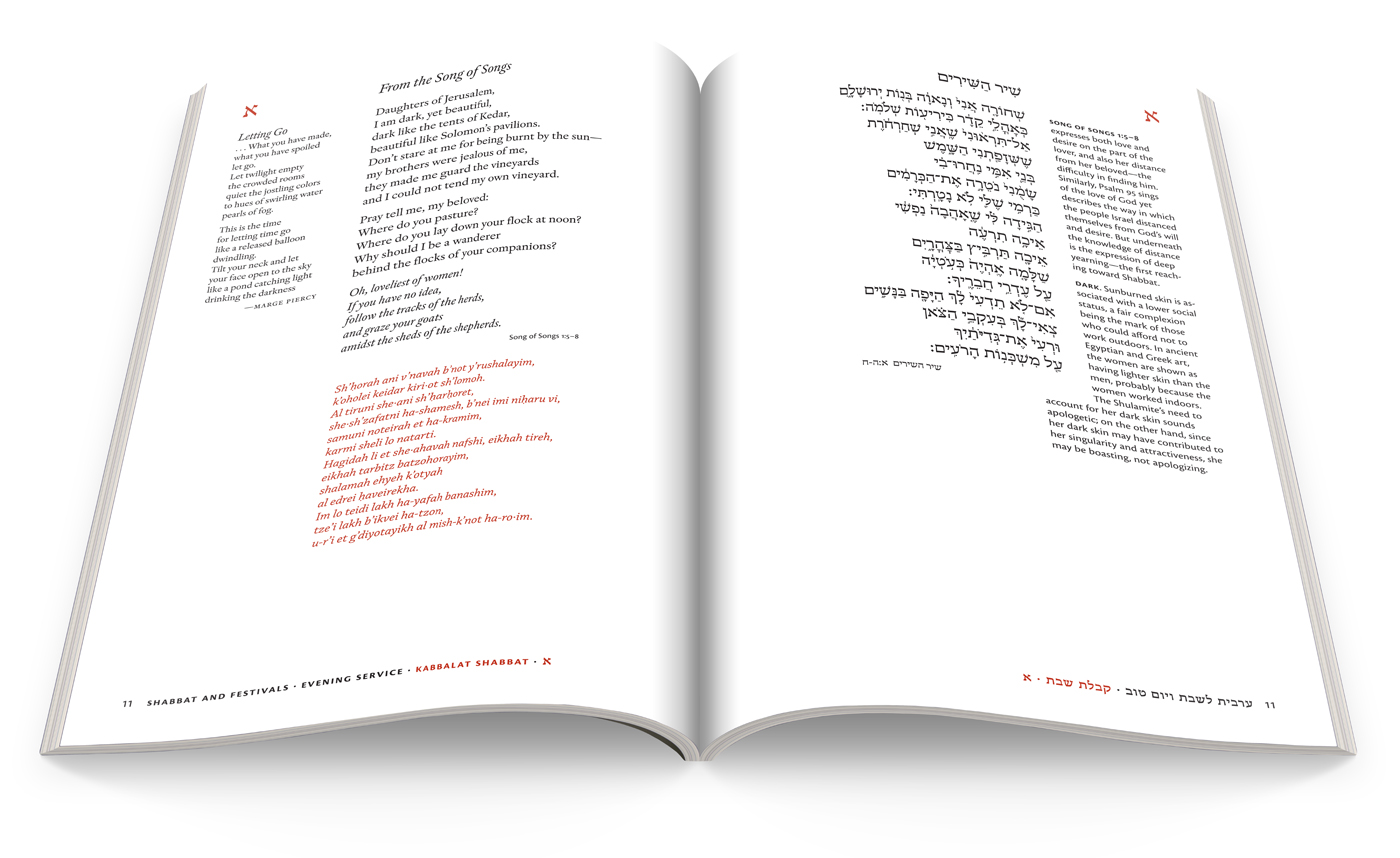

A rendering of pages from the First Fruits: Erev Shabbat preliminary edition [click to enlarge]. The service incorporates sections from the Song of Songs interspersed between the traditional Kabbalat Shabbat Psalms, an innovation of the new siddur.

Add new comment